Just along the river, over the hill and through the picturesque flowing meadows, a rather special estate is nestled in a valley not far from the River Medway. Since it was not a great distance to reach this amazing historical fancy, we decided to take a sneaky little adventure in search of rainbow stones, haunting horrors and potential historical intrigues.

We prepared as always by packing our provisions and readying the crew. Charged with employing an experienced navigator, Audrey carefully selected Squishy Bear for the job, a masterful commander of the map. The route to this stunning seat accommodates all manner of ramblers and cyclists alike. Well trodden country footpaths lead almost unbroken, from Tonbridge, through Haysden Country Park, along the vast serene river and all the way up to Penshurst Place. It is a scenic saunter through the Kentish countryside, and a popular one.

Not much is known of the Penshurst Estate before the 13th century, when building work began on a manor house. An easy half days ride from London, Penshurst was ideal for hunting grounds and leisurely accommodation away from the city.

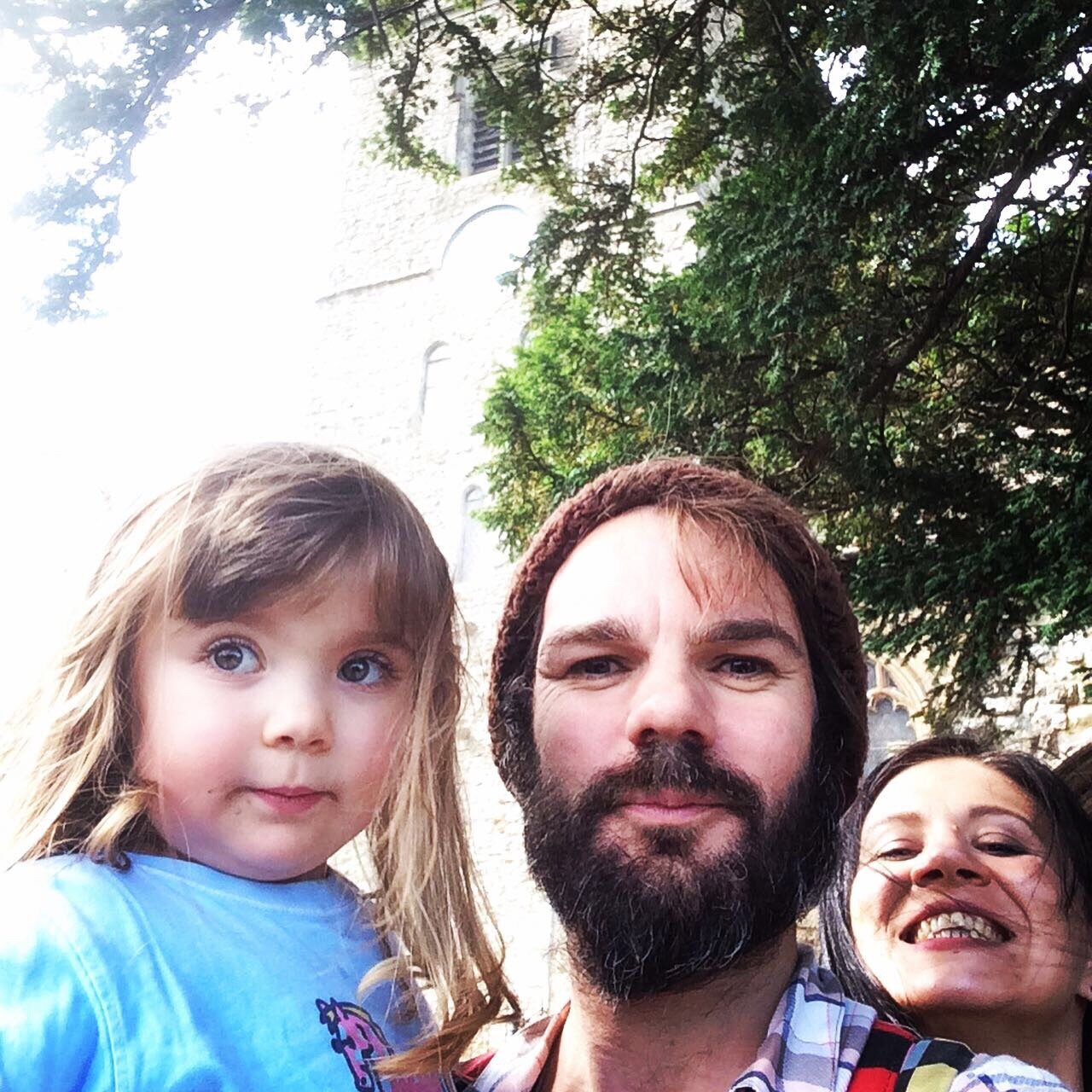

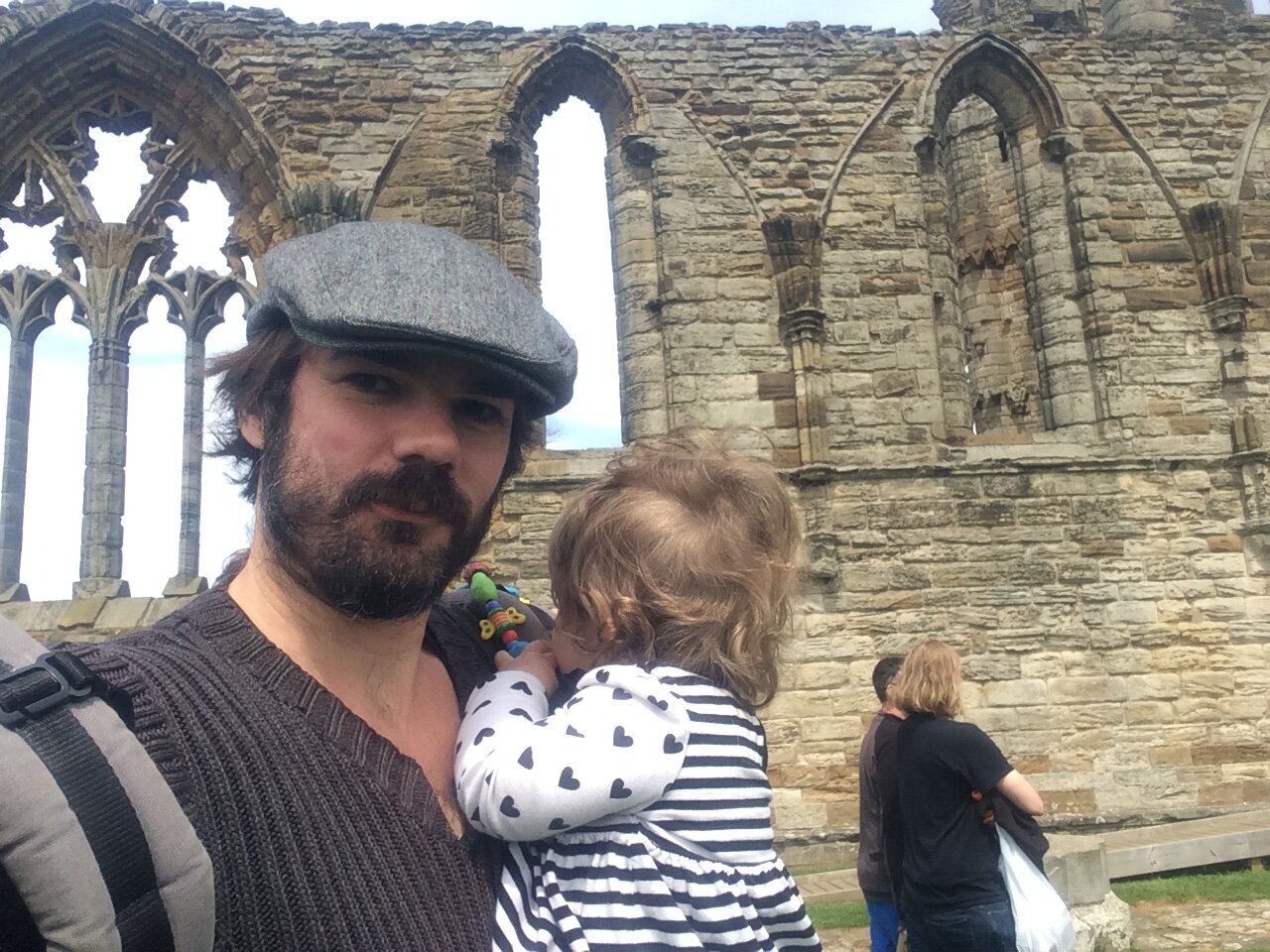

We began our adventure in Penshurst by wandering the church grounds, situated just beside the grand house. The village is brimming with period character, a quaint scatter of old homely architecture with a pub and a collection of shops and homes. According to local legend, a ghostly figure haunts the village, traipsing through the streets on his final journey to see his secret love, the Vicars Daughter! There has been a church on this same spot since at least 1115 AD, but recent Saxon discoveries in the vicinity suggest there may have been some form of religious structure on the site since the 9th century.

The first recorded priest of the church, Wilhhelmus, was appointed by Archbishop Thomas Becket. It would be his final public order before assassination just two days later at Canterbury Cathedral. The church of St John the Baptist at Penshurst has seen continued development through almost every age since the 12th century.

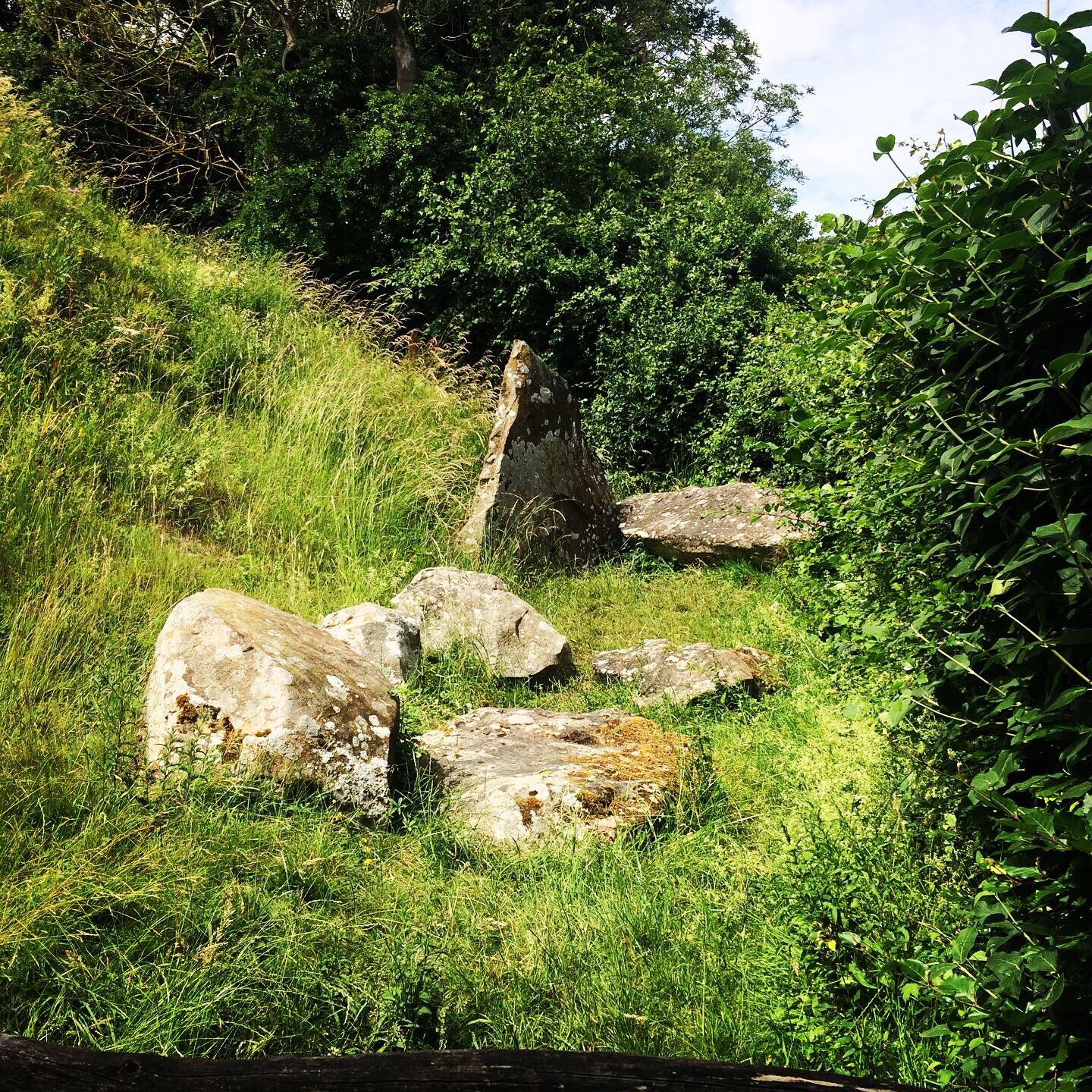

Amongst the throngs buried in its hallowed grounds are Earls, Viscounts, Knights, Leaders of the British Army and a Viceroy of India. Ghosts of the good and great reside here, alongside some of the more sinister deceased residents. The churchyard also houses one of the last remaining Dole Tables to be found in the country, a stone table once used to distribute money and food to those in need.

The church is set amidst the ancient manor house, guild house and rectory, all surviving wonders which have seen a turbulent tour of tragedy and triumph on their doorstep. Our wander took us through the churchyard and out to the spectacular estate beyond, boundless grounds with startling views of the magnificent Penshurst Place.

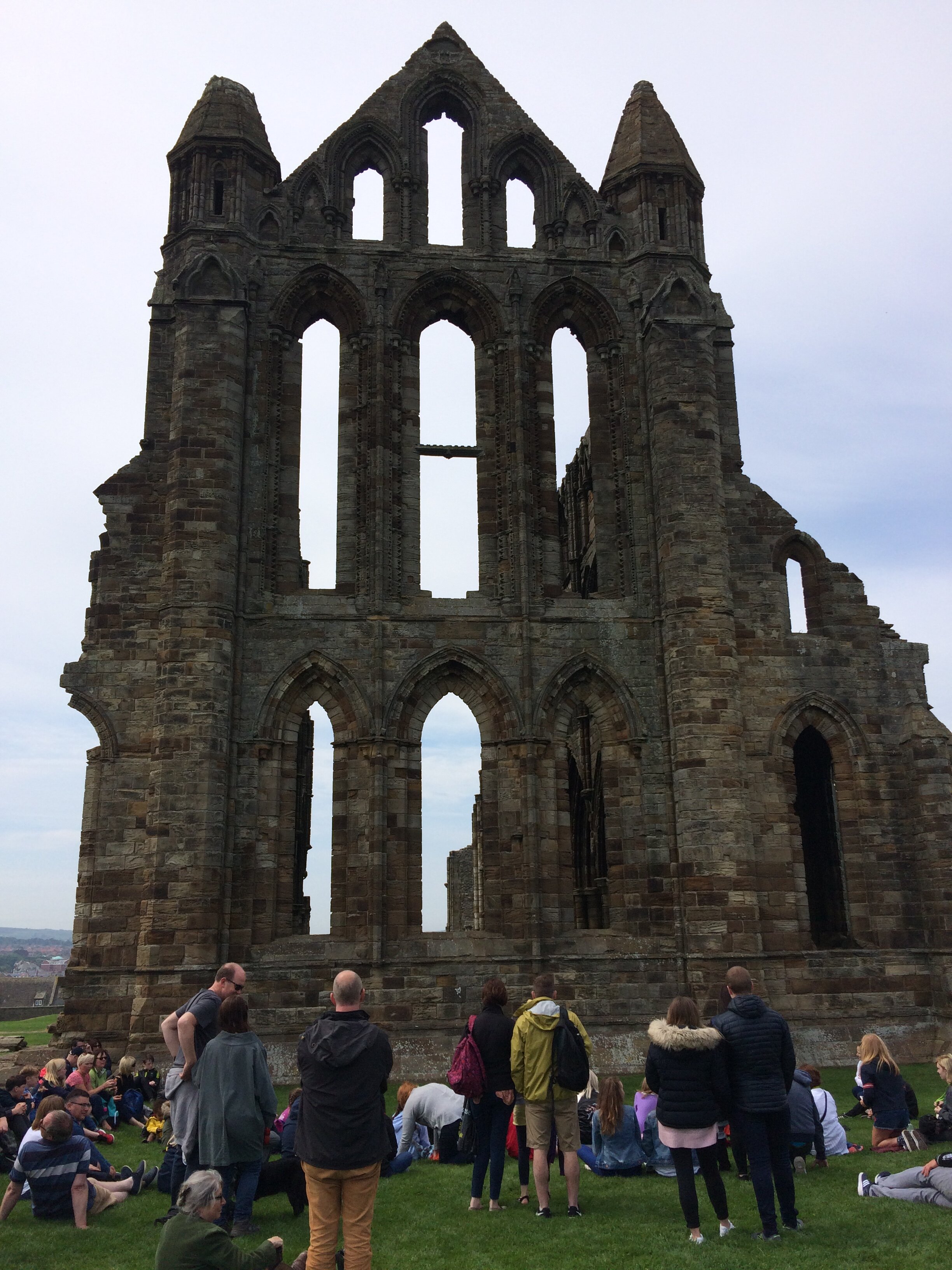

Construction of Penshurst Place began in the 14th century. Sir John De Pulteney desired a country estate to add to his London properties and so had a Manor House built in 1341, much of the house remains today in its original state. Through the centuries, the house was developed with protective towers, curtain walls and ever larger and more luxurious chambers. King Henry IV’s third son, John Duke of Bedford owned the house for a time and in the mid 15th century he added the hall now known as the Buckingham Building.

Humphrey Stafford, the 1st Duke of Buckingham inherited the estate. He was the first of three successive Buckingham’s to own the property. The 3rd Duke enjoyed displaying his wealth and power. In 1519 he invited Henry VIII to Penshurst. With no male heir, Henry feared Buckingham as a threat to his throne and found an excuse to have him tried and executed, seizing the property for himself.

Henry VIII used Penshurst as a hunting lodge, and an excuse to visit his soon-to-be second wife, Anne Boleyn, since her home of Hever Castle was nearby. Sticking with the wives of Henry association, the house would later be gifted to Anne of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife, in their divorce settlement before falling back into the hands of the monopolistic monarchs.

King Edward VI, Henry’s sickly son, gifted the house to his tutor and steward, Sir William Sidney. It would remain in this famous family until the present day. One of the most renowned members of this incredible family was the Tudor poet, Sir Philip Sidney. He was known for his works such as The Defence of Poesy, Astrophel and Stella, and The Arcadia. Philip Sidney was also a soldier and died at just 31, from a bullet wound inflicted during fighting for the Protestant cause against the Spanish at the battle of Zutphen. It is said that the apparition of Sir Philip still stalks the halls of Penshurst, perhaps musing a final powerful poem or lamenting his early jaunt to the grave?

The house continued to grow, seeing visitors such as Elizabeth I and the children of Charles I. It would remain a beacon of literary musings throughout the centuries. Penshurst opened to the public in 1947 and now boasts a visitor centre and cafe, as well as some stunning gardens.

We circled the great house, its astonishing architecture dominating the landscape. From various explorations of the estate during my various exercise adventures, I have noticed a great deal of intriguing monuments littering the land. A strange mound caps the hill, labelled on our trusty OS map, but with little further information as to what it may have been? A landscape folly? A natural phenomenon? A tomb? Nearby is a perfect circle of trees, and throughout the grounds are some incredible flora and staggering stumps. The entire area seems steeped in mythical properties, a fairytale panorama with ghostly greatness in every inch.

Audrey collected an engrossing array of magical twigs and enchanting leaves to add to her ever-growing collection of supernatural specimens. Still no sign of the elusive rainbow stone... perhaps they were hidden within the well-fortified walls of Penshurst Place?

We completed our investigations with a visit to the local pub, a perfect way to end the adventure sat beside an open fire, enjoying an ale or two and resting our weary feet. It had been a fascinating forage through the home of many ancient elites... their treasures are undoubtedly scattered in this lush landscape, and possibly their sinister spooky secrets too...