My dearest Emily,

I find my attention drawn to the fascinating histories of Myanmar. This magical and mysterious landscape has seen millennia of intrigue and evolution, conflict and Kingdoms. The later histories of this incredible land are so littered with stimulating stories, they could be straight from the pages of some fiction novel. My latest curiosity regarded a dethroned King and a stolen treasure hoard.

In 1885, British forces sailed up the River Irrawaddy in Burma to force the abdication of King Thibaw. On 28 November, General Sir Harry Prendergast and Colonel Edward Sladen entered Mandalay Palace and accepted the King’s surrender.

Thibaw’s palace in Mandalay was a magnificent carved and gilded structure with a great seven- roofed spire. Whilst the government reported a largely peaceful and mutual transfer of power, other accounts suggested an unruly takeover. The palace was brimming with priceless treasures, and there was a scramble for its riches as British soldiers took control.

Thibaw was exiled to Ratnagiri in India and saw out the remainder of his life in some degree of comfort. He wrote to King George V, claiming Colonel Sladen had promised to secure his crown jewels for safe custody and return them when it was safe to do so - a pledge he did not keep.

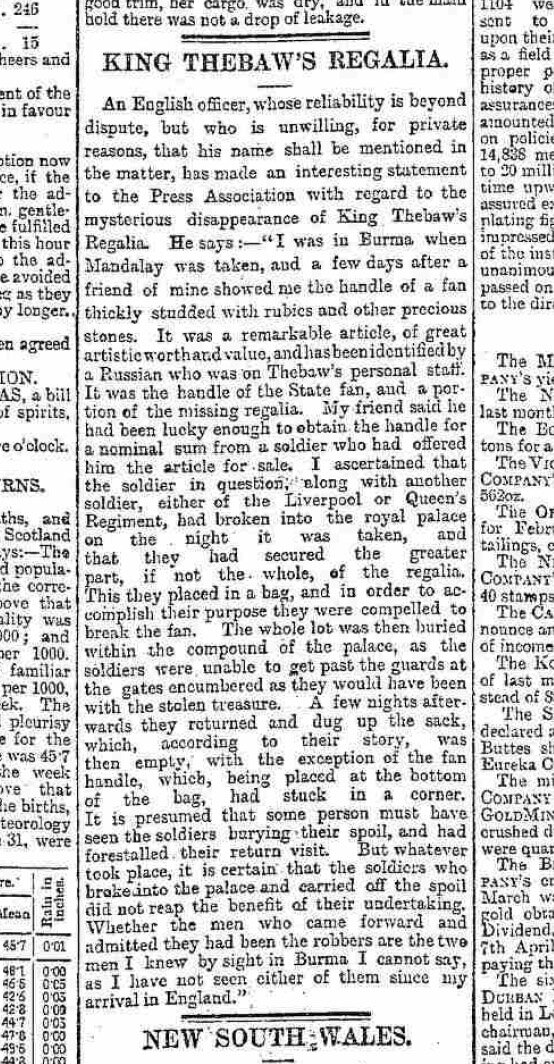

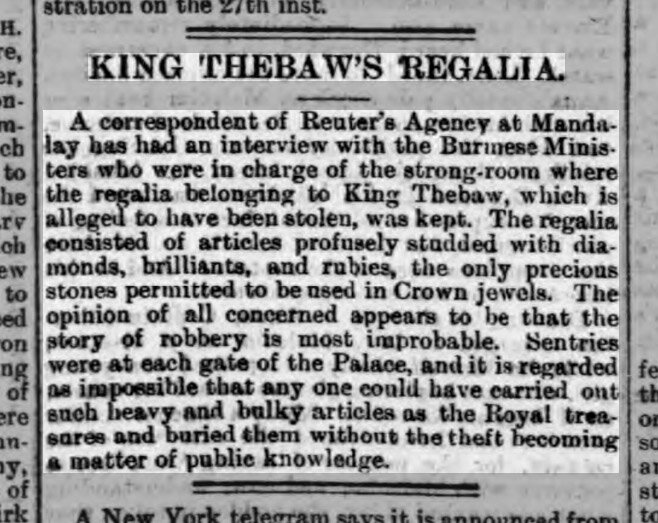

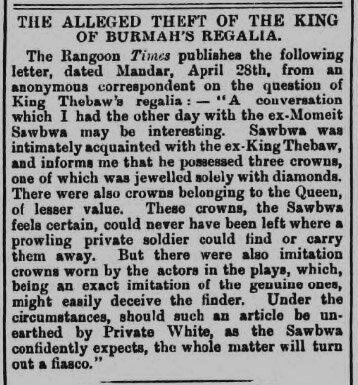

Many of the regalia were shipped to Britain, but some royal treasures simply disappeared. Rumours began to circulate of rogue British soldiers securing a portion of it. They were said to have buried loot in bags within the palace compound, being unable to sneak it past the guards at the gates. Amongst the missing treasures was a gold calf weighing several hundredweight, a crown studded in rubies and diamonds surmounted by a peacock, quantities of precious stones, and an enormous and valuable ruby formerly on the forehead of a giant golden statue of Gautama Buddha.

On 9 January 1893, John Mobbs, an estate agent in Southampton, wrote to the Earl of Kimberley at the India Office regarding a rumour he had heard from a Charles Berry. William White, alias Jack Marshall, was a private in the 2nd Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment. He spent two years in Burma on the signalling staff, spoke the language, and left a wife and son there. White lodged for some time with Berry’s mother-in-law at Wandsworth, and disclosed that he and another soldier had hidden away King Thibaw’s crown jewels and regalia. The second soldier had given a death bed confession, admitting the theft and burial.

White was working in Kent and Surrey as a labourer and dock worker. Mobbs sought him out to ascertain details of his story. White agreed to cooperate so long as the government indemnified him from punishment for the theft. The government, unsure of the situation and unwilling to participate in a treasure hunt, offered Mobbs a percentage of the treasure’s worth should he retrieve it.

The situation was complicated when White decided to retrieve the jewels alone. He deemed the government reward insufficient and intended to move permanently to Burma. Having received his indemnity, he took his last pension payment and disappeared.

Reports stated White left England for Rangoon in May 1894. The India Office did not believe he could recover the hidden treasure without their knowledge, though Mobbs feared some could be accessed with ease.

Information on the hunt is as elusive as the jewels themselves. Where did White go? Did Mobbs make the journey to Mandalay?

The missing treasure also remains shrouded in mystery. Did the Government hide it? Did soldiers retrieve the buried loot? Maybe palace staff discovered it? Perhaps it is buried there still?

Craig Campbell

Curatorial Support Officer, India Office Records

Further reading:

British Newspaper Archive also available through Findmypast -

Illustrated London News 7 April & 14 April 1894

Englishman's Overland Mail 9 May 1894

The Lincolnshire Echo 21 May 1894

The Glasgow Herald 3 April 1894, p.7 and 6 April 1894, p.8

The Sphere 28 March 1959

Southern Reporter 7 June 1894

Photo 312 : 1885-1886 - Burma - One hundred photographs, illustrating incidents connected with the British Expeditionary Force

Photo 472 : 1870s-1940s - Sir Geoffrey Ramsden Collection: Photographs relating to the life and career in India of Sir Geoffrey Ramsden

Photo 1237 : 1885-1886 - Lantern slides relating to the 3rd Anglo-Burmese War

IOR/L/PS/20/MEMO38/14 : 4 Dec 1885 - Memorandum by His Excellency the Governor [on Upper Burma, following occupation of Mandalay by British forces] M E Grant Duff, 4 Dec 1885

IOR/L/MIL/7/9167 : 1885-1888 - Collection 205/7 Reports by General Prendergast and his officers on operations up to fall of Mandalay.

IOR/L/MIL/7/9162 : 1885 - Collection 205/2 Telegraphic reports of operations until fall of Mandalay, November 1885.

IOR/L/PS/20/MEMO38/14 : 4 Dec 1885 - Memorandum by His Excellency the Governor [on Upper Burma, following occupation of Mandalay by British forces] M E Grant Duff, 4 Dec 1885

Mss Eur E290 : 1845-1891 - Papers of Col Sir Edward Sladen